Today being Lammas Day, I thought it fitting that I should head down to the local bakery for some bread and coffee. As I ate my breakfast, I continued my re-reading of G. K. Chesterton’s book on St. Thomas Aquinas. The life of C. S. Lewis never far from my thoughts, I was struck by these lines from a passage describing Thomas’s argument for supernatural revelation:

“His arguments are rational and natural; but his own deduction is all for the supernatural … And when we come to that, we find it is something as simple as St. Francis himself could desire; the message from heaven; the story that is told out of the sky; the fairytale that is really true.”

That phrase, “the fairytale that is really true,” immediately struck me – as it probably strikes you – as the very argument that Hugo Dyson and J. R. R. Tolkien made on that fateful, late-night stroll along Addison’s Walk, with which they sought to convince C. S. Lewis of the truth of Christianity. I could not help but wonder whether Dyson or Tolkien had previously read Chesterton’s words or not. Later, I noted that Chesterton’s book was published in 1933, but the famous conversation actually preceded it – 19 September, 1931. But in the end, it doesn’t matter. The fact that the same words might come from the mouth of Chesterton and Tolkien can easily enough be explained by the fact that men who read similar books and hold similar assumptions and interests are sure to reach similar conclusions.

I have a life-long friend who lives in another state. Because of the distance, it may be years between occasions when we visit. Yet, every time we do meet, we find that we are thinking about the same things. The explanation is patent: simply compare our libraries and listen to our casual conversation. That we are thinking about the same subjects is not surprising. There is no necessity, however, that we should be thinking about the same things at the same time. The coincidence of our interests hints at a supernatural influence.

As for Tolkien and Lewis, there was a disjunction between the time when they would agree that Christianity was a “fairy tale that is really true.” Before September, 1931, though they had read the same kinds of books, they did not have the same assumptions. Tolkien had long before settled on Christian belief. Lewis had resisted it, for various reasons. But on this night, there was something supernaturally at work in Lewis’s heart and mind that would lead to their ultimate agreement.

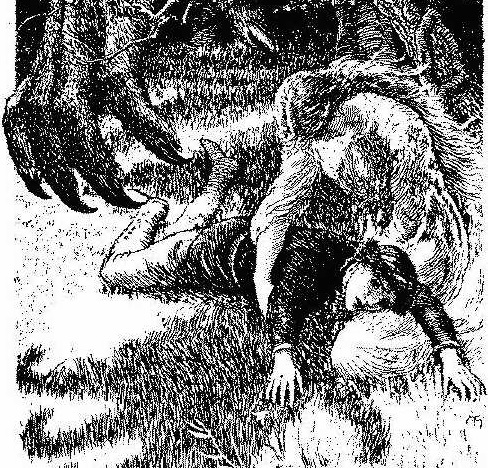

The fact is, Lewis himself because the subject of a fairy-tale coming true – indeed, nothing less than a MacDonald fairy tale at that. Lewis became Anados. He became the subject of a Grace that turned his foolish pride in his opinion into a humble acceptance of Reality, though it meant the death of his old self and the flowering of a new life. And as he existentially went through a fairy-tale-become-true, he found himself agreeing with his friend, Tolkien: it is possible for a fairy tale to be true, and it is certainly the case that Christianity is such a tale.

C. S. Lewis was meant to not only read the same books as his friends, but to know the same Grace. There is much that is miraculous about The Inklings.

————————–

Please note that the content and viewpoints of Rev. Beckmann are his own and are not necessarily those of the C.S. Lewis Foundation. We have not edited his writing in any substantial way and have permission from him to post his content.

————————–

The Rev. David Beckmann has for many years been involved in both the Church and education. He helped to start a Christian school in South Carolina, tutored homeschoolers, and has been adjunct faculty for both Covenant College and the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga. He founded the C.S. Lewis Society of Chattanooga in 2005. He has spoken extensively on C.S Lewis, and was the Director of the C.S Lewis Study Centre at The Kilns from 2014-2015. He is currently a Regional Representative for the C.S. Lewis Foundation in Chattanooga.

The Rev. David Beckmann has for many years been involved in both the Church and education. He helped to start a Christian school in South Carolina, tutored homeschoolers, and has been adjunct faculty for both Covenant College and the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga. He founded the C.S. Lewis Society of Chattanooga in 2005. He has spoken extensively on C.S Lewis, and was the Director of the C.S Lewis Study Centre at The Kilns from 2014-2015. He is currently a Regional Representative for the C.S. Lewis Foundation in Chattanooga.