C. S Lewis was an intellectual. Therefore, when he came to the Christian faith, he approached Christian belief intellectually. It is no surprise that he ran into problems!

In Letter 11 of Letters to Malcolm – which is the substance of chapter 15 of How To Pray – Lewis tries to deal with a problem concerning the Bible’s teaching about prayer that troubled him for many years. The problem is simply this: We are given an example of prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane, where Jesus makes his petition known to His Father, but he does so with a reservation: “not my will, but thine be done.” In this case, the supplicant knows what he desires, but is not certain of what God’s will is in the matter. However, in St. Mark 11:24, we read, “Therefore I say unto you, What things soever ye desire, when ye pray, believe that ye receive them, and ye shall have them.” In this case, there is a one-to-one relationship between what is asked and what is received. There is no question as to any divine options involved. One’s faith need have no reservations. How does one reconcile these two views of the nature of prayer?

Ten years before writing Letters to Malcolm, on the 8th of December, 1953, Lewis addressed a group of clergy about Mark 11:24, and in the end he asks them for help. He in effect says, “You are the theologians. I need help here. How does it work?” You can read his address in the book Christian Reflections, in the chapter entitled “Petionary Prayer: A Problem Without an Answer.” He does not seem to have received an answer from his audience.

But Lewis did not give up trying to find an answer. It is amusing to read his comment about how a more “liberal” theologian may have handled the subject. A modern theologian may have simply dismissed the problem by ignoring any inconvenient statement in the Bible, saying that they did not know what they were talking about. Lewis contradicts this approach by saying that detectives in crime novels can sometimes be better thinkers than the theologians. He then proceeds to almost quote verbatim Sherlock Holmes from “The Beryl Coronet”: “It is an old maxim of mine that when you have excluded the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

With such dogged determination, Lewis worked on this problem over the years. Here he – tentatively – gives his best answer. Perhaps this kind of confident faith in asking, which stands on such a bold promise as we find in St. Mark, is a gift God gives to his friends in a time of need. When there’s an important event going on and his servant has to have this level of an assurance, he grants it to them. Otherwise, he would pray in what could be thought a more normal fashion: “not my will but thine be done.”

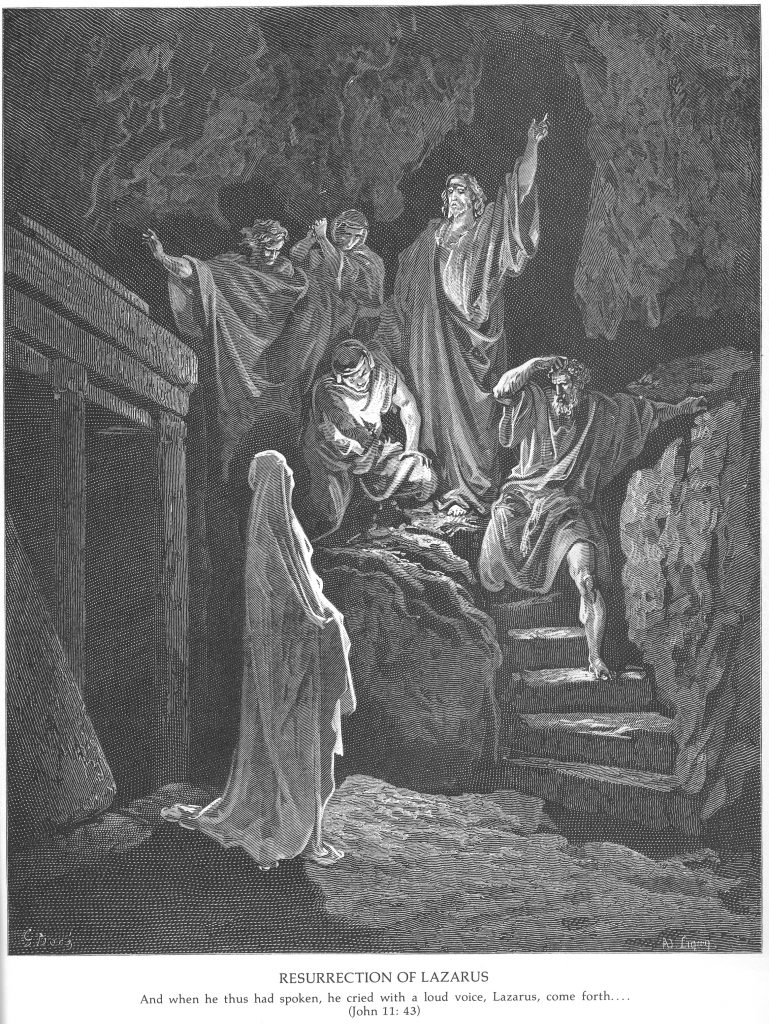

I think we can find a case for this in the life of Christ himself. Lewis has already raised the example of Jesus in the garden, praying a more “ordinary” prayer – though under extremely unordinary circumstances! Yet, in John 11, before Lazarus’s tomb, we find him praying with a much greater assurance and certainty. We read:

41 Then they took away the stone from the place where the dead was laid. And Jesus lifted up his eyes, and said, Father, I thank thee that thou hast heard me. 42 And I knew that thou hearest me always: but because of the people which stand by I said it, that they may believe that thou hast sent me. 43 And when he thus had spoken, he cried with a loud voice, Lazarus, come forth.

Here Jesus is in a very public position. Everyone is watching to see what he will do. He has to be able to know that, when he calls Lazarus, he will come forth. Apparently, before reaching Bethany, Jesus had already been praying and asking his Father for this to happen. He says in v. 41 “I know you have heard me.” See the assurance here. Jesus knows what God’s will is in this situation. He needed to know this because his reputation is going to be on the line. He had to be certain that Lazarus would rise before he calls him to do so. Therefore, God provided him with the certainty of his faith, which he so required.

Lewis says more on the issue, but this is a sample of how he tried to deal with the problem. He thought there must be levels of faith and prayer. This differentiation is helpful to understand, because some of us are told we are supposed to always maintain a faith that is full of certainty, or there is something wrong with us It’s as if they think Mark 11:24 is all the Bible says about prayer. Not so. Just look at the prayer life of our Lord.

Reference: C. S. Lewis, How To Pray: Reflections and Essays, (New York, HarperOne, 2018), ISBN-13: 978-0062847133.

————————–

Please note that the content and viewpoints of Rev. Beckmann are his own and are not necessarily those of the C.S. Lewis Foundation. We have not edited his writing in any substantial way and have permission from him to post his content.

————————–

The Rev. David Beckmann has for many years been involved in both the Church and education. He helped to start a Christian school in South Carolina, tutored homeschoolers, and has been adjunct faculty for both Covenant College and the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga. He founded the C.S. Lewis Society of Chattanooga in 2005. He has spoken extensively on C.S Lewis, and was the Director of the C.S Lewis Study Centre at The Kilns from 2014-2015. He is currently a Regional Representative for the C.S. Lewis Foundation in Chattanooga.

The Rev. David Beckmann has for many years been involved in both the Church and education. He helped to start a Christian school in South Carolina, tutored homeschoolers, and has been adjunct faculty for both Covenant College and the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga. He founded the C.S. Lewis Society of Chattanooga in 2005. He has spoken extensively on C.S Lewis, and was the Director of the C.S Lewis Study Centre at The Kilns from 2014-2015. He is currently a Regional Representative for the C.S. Lewis Foundation in Chattanooga.