[The British people crowd into their churches for the National Day of Prayer, 26 May, 1940, to pray for the BEF in France.]

The evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from Dunkirk in May/June 1940 was a gift from God that moved the whole of Great Britain. Hundreds of thousands of families were touched by the deliverance of their relatives from death or cruel, indefinite imprisonment. The prayer of the nation, lead by their king, seemed to have been answered, and the whole nation thanked God for it.

C. S. Lewis was one of those who had a personal involvement in the event. His brother, Warnie, was over in France with the BEF. Thankfully, he was brought safely home.

The rescue of the BEF has always been called a “miracle.” The confluence of the circumstances was indeed remarkable, and to the eye of faith, “God fought for us” (Henry V, Act IV). In Appendix B of Miracles (reprinted in the new How To Pray, chapter 5), Lewis asks if it is correct to say that the evacuation was a miracle, or whether it can be so definitely said that it was an answer to prayer. He also contests the idea that the evacuation was a “special providence” of God, in distinction from his normal providence in our lives.

The question is asked, why? Why did Lewis contest this popular idea – that God had done something special for England? As I think back over the essay and read accounts of the event, I think that Lewis is simply trying to shore up the position of the Church on the issue to prevent skeptics from finding fault with our views about such events. He recognizes that, to the skeptic, the coincidences of the elements which helped the BEF to get away were remarkable, but they were all, nevertheless, of the same cause-and-effect nature as any other event in history. There is no need to appeal to some supernatural miracle to explain it. England was just lucky.

An example of such skepticism is Major General Julian Thompson, in his book Dunkirk: Retreat to Victory. He writes, “The evacuation of the BEF at Dunkirk was spoken about as a miracle at the time, and still is depicted in those terms to this day. The only miraculous element in the operation was the weather…. The Dunkirk operation owed its success to the power and skill of the Royal Navy, not to any mystical intervention” (Kindle location 6026).

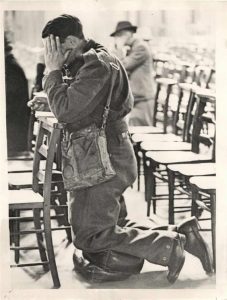

[British soldier during a service of intercession for France at London’s Westminster Catholic Cathedral. 1940.]

Lewis defines a miracle as an event initiated supernaturally by God which enters into the flow of cause-and-effect history. The event takes up its place as any other event, only it has not been “caused” by the interlocking sequence of preceding events. An example would be the immediate calming of the waves by Jesus on the sea of Galilee, of which we read in Mark 4:39. There was no other explanation for such immediate and unnatural calming of the weather and the waves except a real intervention in time and space from God. In the case of Dunkirk, however, it had happened before that the weather was good and the Channel was calm. And the weather during those days in 1940 could be traced to the weather that had preceded. There was nothing about the weather that could not be the result of normal cause and effect. If one only looked at the circumstances, there was no objective evidence that a miracle had occurred, and there was no logical necessity that the weather was due to a “miraculous element.”

Lewis explains that one’s interpretation of Dunkirk was a decision of the will, based upon a presupposition of either faith or unbelief. To the eye of faith, God had intervened, whether you call it a “miracle” or, if short of an actual “miracle,” at least an answer to prayer. But if one believed so, he must not point to such a remarkable event to “prove” that God answers prayer and intervenes in events. If one attempted to do so, he would be in an untenable position in debate with a skeptic. Lewis wants to keep us from being in that kind of position.

It is because Lewis is trying to be careful as an apologist that he writes about Dunkirk. He discourages the use of the word “miracle” with reference to Dunkirk because, according to his definition, the term does not fit. He would rather we call it a Providential answer to prayer, with the caveat: to the eye of faith. The skeptic would not be able to argue against that position (all opinions are logically valid). Rather, the conversation with a skeptic about Dunkirk would need to backtrack to matters of the nature of what we call History. But our honesty about our inability to “prove” an answer to prayer by the confluence of circumstances alone would enable the conversation to move on to such a subject.

It never helps to try to make something you wish could argue for Christianity to do so, when it really does not.

[Image sources: http://www.anglican.ink/article/national-day-prayer-time-dunkirk-1940; Pinterest]

Reference: C. S. Lewis, How To Pray: Reflections and Essays, (New York, HarperOne, 2018), ISBN-13: 978-0062847133.

————————–

Please note that the content and viewpoints of Rev. Beckmann are his own and are not necessarily those of the C.S. Lewis Foundation. We have not edited his writing in any substantial way and have permission from him to post his content.

————————–

The Rev. David Beckmann has for many years been involved in both the Church and education. He helped to start a Christian school in South Carolina, tutored homeschoolers, and has been adjunct faculty for both Covenant College and the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga. He founded the C.S. Lewis Society of Chattanooga in 2005. He has spoken extensively on C.S Lewis, and was the Director of the C.S Lewis Study Centre at The Kilns from 2014-2015. He is currently a Regional Representative for the C.S. Lewis Foundation in Chattanooga.

The Rev. David Beckmann has for many years been involved in both the Church and education. He helped to start a Christian school in South Carolina, tutored homeschoolers, and has been adjunct faculty for both Covenant College and the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga. He founded the C.S. Lewis Society of Chattanooga in 2005. He has spoken extensively on C.S Lewis, and was the Director of the C.S Lewis Study Centre at The Kilns from 2014-2015. He is currently a Regional Representative for the C.S. Lewis Foundation in Chattanooga.